From Digital to Analog

Karlheinz Essl in conversation with Florian CramerRadio WORM, 23 June 2023

A one-hour conversation with Karlheinz Essl on his musical composition, freely sharing his work online since the early 1990s, developing the Realtime Composition Library (RTC-lib) for Max, the relationship between indeterminacy and computer-generated music, his homage to Throbbing Gristle, geopolitical crises that made him turn to improvised music with analog synthesizers.This interview was recorded on June 21st, 2023 via Zoom for a radio show on Radio WORM, broadcasted on June 23rd, 2023.

Talking about the beginnings of Karlheinz Essl's career as composer working with computers since 1985, his involvement with the World-Wide Web where he publishes all his work since 1995, and the development of his open source software RTC-lib for Max which began 1991 at IRCAM, Paris.

His most recent piece Throbbing Crystal, however, was performed on a modular analog synth where Essl attempted to create live electronic music without computers using paradigms of non-linear chaotic systems and audio feedback.

Florian Cramer is a practice-oriented research professor for autonomous art and design practices at the Willem de Kooning Academy, Rotterdam, Netherlands. In the mid-1990s, he was also among the first people who experimented with bringing computer-generative poetry to the World Wide Web.

Karlheinz Essl at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse für Neue Musik 1990

Florian Cramer: Yes, I regularly follow what you publish on your website. I always thought you were the first composer to put practically all of his work on the web since the 1990s.

KHE: Yes, that's actually true. This was my attempt to escape the ivory tower. And with the new media, what we call new media, which is old media nowadays, the Internet and the World Wide Web, it was a very interesting platform to do that.

FC: I think you started as early as in 1994 or 1995, right?

KHE: Yeah, that's true. I think when I came back from IRCAM in 1993, I immediately got an email address in Austria, which was very difficult at this time. My first email address was French, actually, an IRCAM address. And then I already started to put all my work in hypertext format because I was so fascinated by HyperCard. You know this project with Lexikon-Sonate and the electronic Lexikon-Roman of Andreas Okopenko where we used HyperCard. And then when World Wide Web came out with the web browser Mosaic, it became very clear for me that the technology that is now available was also already known by me.

KHE: Actually, I was studying with Friedrich Cerha, who recently died with nearly 100. But the most important person for me who influenced my compositional thinking was Gottfried Michael Koenig.

FC: Yes, who is a big name here in the Netherlands. Among other things, he was one of the founders of the Institute of Sonology in The Hague which left its mark on the entire Dutch scene of electronic and electro-acoustic composition.

KHE: I came in contact with him in the middle of the 1980s while I was visiting my friend Gerhard Eckel, who is now a professor of electronic music in Graz, during a student exchange in Utrecht at Sonology. I came to visit him and by this occasion I met Gottfried Michael Koenig. We became friends and had a very intensive exchange by mail. So we wrote letters to each other. I was always asking questions about his compositions (namely his String Quartet 1957) and his concepts. He was always very generous in answering all my questions. At this time I was at the end of my academic studies in Vienna, and Koenig opened me new horizons towards algorithm composition, which became a major issue for me until now.

Karlheinz Essl at IRCAM, Paris

Foto © 1993 by Sophie Steinberger

KHE: This is how it came into being. I was working at IRCAM between 1991 and 1993, invited as a composer to write the piece Entsagung for ensemble and live-electronics for the newly developed IRCAM Signal Processing Workstation (ISPW), which was based on a NeXT machine, a wonderful black cube equipped with the best microprocessors that you can dream of. Pierre Boulez demanded a real-time composition system for his piece Répons. He needed a portable system [the previous 4X developed by Giuseppe di Giugno was running on a PDP11 mainframe computer] that could be used for live performances on stage. So they built it in this NeXT machine, a commercial computer developed by Steven Jobs. And they put in some specially produced sound cards with signal processors, which was able to generate sound in real time. However, for the sound generation, you need a software. And this software (called "Patcher" these days) later became Max. So I was using Max at the stage when it was not available on the popular machines like like Macintosh or Windows.

When I was working there, my friend Gerhard Eckel was a researcher at IRCAM. We discussed the system and said, okay, it's a fantastic machine, and you have a possibility to do a lot of things, but you have no compositional tools. The tools are basically very technical, but everything that deals with compositional ideas was missing. So we decided to construct some functionalities and software extension that could be used by me or by others in different contexts. So in fact, everything I did before on my Atari ST computer on a computer aided composition system that I developed in Logo in the mid 1980s, I was porting into the real-time domain to this IRCAM machine.

FC: Maybe we need to unpack that, because not every one of our listeners will be familiar with all the backgrounds and terminology. Pierre Boulez, who you mentioned as a composer, founded the studio and experimental music research institute IRCAM, which still exists today. It's very institutional and very well funded. Here in the Netherlands we had STEIM and CEM, both lower-tech, less institutional alternatives to IRCAM. WORM's electronic music studio grew out of CEM and housed its equipment for many years. Pierre Boulez, the founder of IRCAM, was a major figure in contemporary classical music, both as a composer and as a conductor. He belongs to the same generation as, for example, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig.

You mentioned the term real time several times... From the 1950s to the 1980s, composers like Lejaren A. Hiller and Boulez could not use computers as real-time electronic instruments. Instead, they had to first write a musical composition as a computer program - or algorithmic score - without actually hearing what they were composing. Then they would run the program on the computer and play the music. The principle is the same as programming a player piano or musical toy like a music box with a punch card, where you have to code the composition first and then play and hear it. Real-time, however, means that you can compose and manipulate the sounds as they're being played. The computer actually became a musical instrument, not just an algorithmic player piano. This was a huge breakthrough.

The NeXT computer was developed by Steve Jobs after he was fired from Apple. He started a new company to build a high-end computer with a UNIX-based operating system. It was later bought by Apple and developed into Mac OS X. The NeXT machines were among the first computers powerful enough to allow algorithmic electronic music composition in real time. That was when you came along and developed the RTC-lib. It allowed people to use a set of musical expressions in their algorithmic compositions instead of having to code everything from scratch. So the RTC-lib is an abstraction layer that allows people to work with the computer like a music composer and not like a computer programmer.

KHE: In fact, the ideas of creating such a modular system was highly influenced by people in Holland. When I was there in 1986 at the 12th Computer Music Conference in The Hague I came across Peter Desain and Henkjan Honing who created an algorithmic composition environment LOCO written in Logo, a computer language which was developed at MIT for children. These guys made fascinating algorithmic works for little percussive instruments, which were triggered by machines, which, in turn, were controlled by these algorithms. When I came back home, I started to create my own algorithmic composition system for instrumental music, not electronic music, using the same sort of programming language, Logo. And when I came to IRCAM and found out that nowadays you can do everything in real time, that means that you can immediately listen to the results, it changed everything for me and also changed my life as a composer. Before I was sitting at home on my desk writing scores, which was a very tedious work, and it took always very long before they became played and performed. And then with this experience of a performance, I could maybe change the score afterwards. But now it was possible to create music directly on the fly, listening what's going on and adjusting the system.

FC: You mentioned Logo. It was originally developed as an educational programming language for children, working with an animated "turtle" on the screen. You could call it a gamified programming language. But it was also a step towards composing electronic music in real time on a computer. And while we mentioned that you've been publishing all your work on the web since the 1990s, we should also mention that this included the real-time composition library, if I'm not mistaken.

Computer graphics generated with Karlheinz Essl's COMPOSE software environment

FC: So there was a whole community behind it. It's comparable to Linux, which came out at exactly the same time, with the first version of the Linux kernel released in 1994. So like Linux, it was a collaborative and community-driven collective development that was made possible by the Internet, because for the first time people could download code, share it, and work on it together. And I think your RTC library is still in use today - you're still working on it, aren't you?

KHE: Well, this is a long story. I always have to take care about the different versions of processors, Max versions, and also the different platforms and operating systems. Now my library runs on Windows and macOS. Apple has changed its hardware architecture recently to ARM processors. So some of the so-called externals had to be recompiled, and this took quite long, but it's completed now. It's now part of the Max distribution, so you have this possibility to download it directly from Max with the so-called Package Manager. And I use it also for my own work, of course, but also my students use it as basic software tools for their compositions.

FC: You mentioned earlier that you have collaborated with other artists. For example, you worked with hypertext and the program Hypercard, among others, with the Austrian literary writers Andreas Okopenko and Ferdinand Schmatz, a major contemporary experimental poet.

KHE: I was very much attracted by the rudeness of their sound and the performances they did. And once, I don't know when it came out, maybe around 2000, there was a really big CD box with all their works. I found them always very interesting, also the way how they produce their sounds with self-built devices. But the point is, that's very important to mention, that I was working in the digital domain for more than 35 years. And last year in summer, I felt in a deep crisis of meaning, not at least due to the war in Ukraine, where I was questioning a lot of things, asking myself as an artist, how can I go on like this?

I mean, it's impossible. Was it Adorno who said after Auschwitz, you cannot write poems? I had a similar feeling that everything I was doing now is completely meaningless. And I tried to find a way to escape this depression. And so I asked myself, is it possible for me to create electronic music without computers and without all the tools that I've developed? And then I came to this conclusion that I have to go back to the old days before the computers were existing: analog systems, synthesizers.

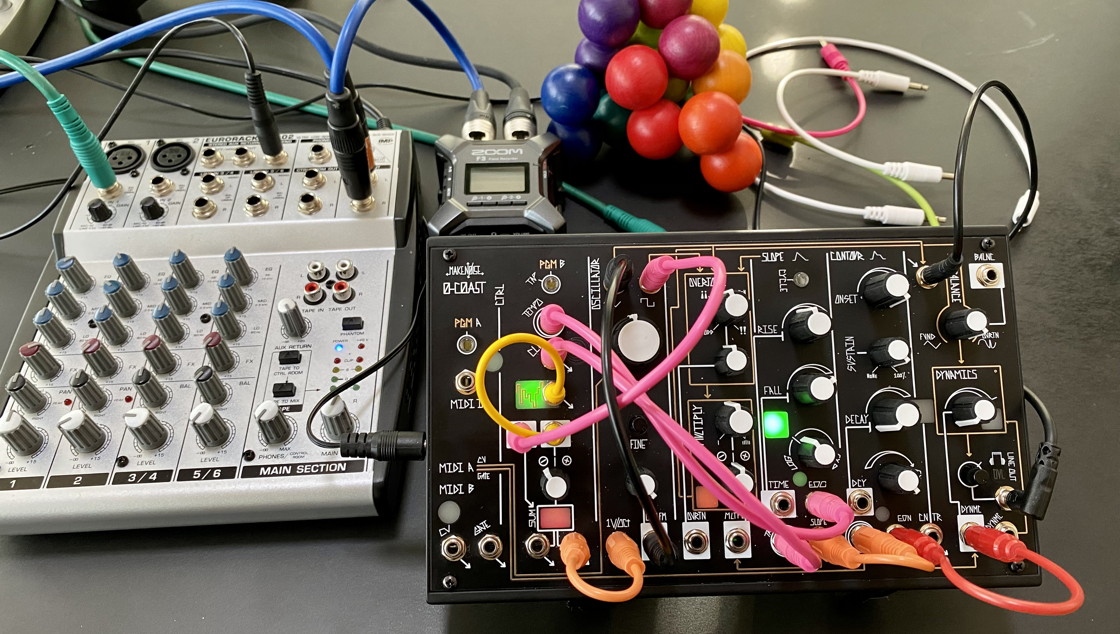

Setup for Coastlines with a MakeNoise 0-COAST synth and an analog mixer

When I was a teenager and played in a rock band, I also dreamed of having a synthesizer. Actually, I never had one. In the electronic studio of the music university in Vienna, there were some modular synthesizers, and I experimented with them. And at a certain time, I wasn't interested anymore, because I found it much more interesting to work with computers and create my own environments instead of being subordinated to concepts that somebody else had in creating a machine like a Moog synthesizer. And one thing I always abhor is the presence of a keyboard, because it is a reference to a type of music which does not belong to electronic music in my understanding. White and black keys and 12 tone equally tempered scales and those things. And then I came across a small modular synth that I bought many years ago, a Doepfer DARK ENERGY. And I started to dig it out and try again and found out it's very difficult to get some sound out of it because it needed a keyboard. And then I found out that it's even possible using a keyboard and patch it in a way that the keys that you play on the keyboard are not producing the pitches. They're just triggers and the pitches are produced by something else, maybe by the pressure of the keys. I had a small keyboard attached to this synthesizer, but it would not play notes, but creating some very bizarre sounds and I could manually do something on it. Although I found some quite interesting things, I came to a point where I thought, okay, I need more. I need some randomness, which is not part of this system.

I discussed this with my friend Gerhard Eckel, and he mentioned a device that's built by a small company in the US, Make noise. It's called 0-COAST modular synth. Why 0-COAST? Because it's neither east or west coast, neither Moog nor Buchla, but something in between, that combines both worlds. It's a machine with lots of patch cords and lot of knobs with a very strange and bizarre architecture, which is completely against everything that you normally learn. But this gave me the possibility to create some very, very interesting things by creating so-called chaotic systems with signal feedback that would create a sort of instable equilibrium. With this instrument, I created a series of pieces, which is a work in progress called Coastlines.

Setup for Throbbing Crystals with Doepfer DARK ENERGY analog synth,

a MIDI keyboard controller and a small analog mixer

Let's go back to my piece Throbbing Crystals. A few weeks ago, I was trying to get back to this aformentioned Doepfer DARK ENERGY modular synthesizer. And I tried to re-revive this beast. With all the knowledge that I gained by creating this chaotic feedback systems on my 0-COAST synth, I was going back to the Doepfer and found out that you can create fantastic things. And then - in one day - I recorded the four movements of Throbbing Crystals

FC: Maybe we should listen to the first one now, and then continue our conversation.

Throbbing Crystal, 1st move

FC: We just listened to the first movement of Throbbing Crystals. There seem to be two layers of meaning in the title. We already talked about Throbbing Gristle, the seminal industrial noise band of the 1970s. But crystals also seem to refer to circuits, I guess, to computer chips...

KHE: No, I was thinking about crystal structures like with Anton Webern. Everything is a crystal which you can watch from different angles, and it will always change its appearance. Like a diamond, that changes its color when you move it in a light beam. This is the performance part of this piece. By playing it, you constantly change the perspective and create new ways of sounds in this case. And of course, it's a pun with words because "gristle" and "crystal".

FC: I learned that the band name Throbbing Gristle has an obscene meaning in the dialect of the region where the musicians came from.

KHE: Yeah, of course, that's very obvious. Maybe not so much in my music ;-)

FC: Genesis P-Orridge, in their later life, became a queer icon. I think many people here in the WORM community are familiar with their work, but perhaps with very different historical phases and aspects of it. Younger people may rather know Genesis P-Orridge as a queer transgender performance artist while older people know them for the industrial noise music of Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV. But I find interesting is that you to be going back to a similar technology that Throbbing Gristle used. One of the band members, Peter Christopherson, was a tinkerer who built his own synthesizers. And was probably driven by similar considerations to yours, of avoiding conventional sounds and tonality.

KHE: Well, I must confess that I'm not very familiar with the work of Throbbing Gristle, except that I heard some of their music. But when I was listening afterwards to what I recorded on my Doepfer, I encountered an aspect of pulsation, repetition, something throbbing. And then the title "Throbbing Crystals" came into my mind. Of course, with some reference to this to this fantastic noise band.

FC: You described how you went from computer generated music to live improvised analog modular synthesizer music. I'm also seeing that as a larger cultural trend. Here at WORM, we have a well-equipped analog synthesizer studio that is completely overrun with musicians and booked out for months if not years. There's a largerbigger trend that I've seen in electronic music over the last ten years or so where people are going back to working with modular synthesizers. As a result, they're being manufactured again. Even big companies like Behringer, for example, are now making analog modular synthesizers. It has become an industry of its own. What do you think about that?

KHE: Well, I'm following this from a certain distance, to be honest. And I see a lot of males sitting in front of their machines, very impressive, with lots of cables. It's like showing your new Porsche, in a way. But I am always using very small things, like the 0-COAST synth which has the size of a book. The Doepfer is a little bit higher, but also very small, you can easily put in your pocket. I try to be as minimalistic as possible, and with this reduced means, I try to create a lot of things that are fascinating for me and maybe also for others.

KHE: Yes, because I'm always thinking as a composer who has experiences writing string quartets and orchestra pieces. It's very different. It's not just doing something blindly as there is always a structural component and connotation. When I improvise, I need to get into a state where you don't need to think. You're just here and you have your knobs and turn them. The thing is, in the systems that I'm working with, the functions of these knobs are not always clear. I mean, the sound that you get depends on the combination of so many parameters. It might happen that a certain knob that does something special would behave completely differently in another setting. So everything is highly depending on each other,as often in chaotic systems. So that means that a small turn of the screw could create nothing or everything, and make an explosion. And this is so interesting that you don't know exactly what you're doing. I mean, I'm always preparing things, checking out, experimenting, rehearsing. But in the moment where I make a recording, I'm just trying to concentrate myself, putting myself in a sort of trance by using some methods like Autogenic training. And then I start playing without thinking.

FC: I am reminded of this legendary concert by John Cage and Sun Ra in 1986.

KHE: I don't know about that. John Cage was not an improviser...

FC: That's a good question... But what I've heard, or maybe it's a myth he's perpetuated about himself, is that he claimed he never listened to records of his music because he didn't like the repetition. It was indeterministic music, so it should never sound the same. Records invalidated that. And that, I think, may have been your point of departure for creating generative music, using programming systems like Max to make it actually possible to reproduce aleatoric indeterministic music as what it is, as something that was generated live, by downloading it as a player and listening to what it generates in real time, so that the music would virtually never repeat.

My impression is that a lot of people who did not have a background as studied composers became DIY composers at that time, because one of the barriers to entry had been removed. Suddenly, in the 1990s, there was an explosion of composers, many of them with non-academic backgrounds, thanks to these new technologies. Maybe it's similar to how digital cameras suddenly democratized photography and how desktop publishing democratized graphic design. The same thing happened with systems like Max, thanks to the libraries you programmed.

KHE: But it's like with digital cameras. Everybody has one, but in order to make good photos, you need more than a camera.

FC: Yes, of course. But at least what I observe in the case of photography and filmmaking is that it has allowed people who did not have access to these resources before, including educational resources, but who had the visual talent, to come out and produce. Among other things, it allowed visual artists to make video works with inexpensive technology that could be shown at film festivals. It seems to me that the same thing happened with computer-generated music around the same time. It opened up a new field and gave other less privileged people access to a community. I'm not even talking about the music industry, because experimental music is not something you can make a lot of money with, I guess. Which is also a problem. Electronic experimental studio music is so strongly associated with academia because academia has been one of the few structures supporting this kind of music since the 1950s. Is that true?

KHE: Yeah, but this changes everywhere at the moment. I mean, when I was studying in the 1980s, there was a very narrow framework what a composer is allowed to do and what not. And this is not the case anymore. Also in my university. So aesthetically, it opens up a lot. And people also with other experiences are now given the possibility to study.

FC: Indeed, I also see this, for example, in your old study program of Sonology, which now has a very different demographic of students. I actually meet some of them quite often. They're active here at WORM, for example in the feminist electronic music community Re:Sister, which was founded by Sonology students.

KHE: Well, this had to do with my first subject of study. When I was a teenager, I was in a school for chemistry. So I'm a trained industrial chemistry engineer. I was always fascinated by the alchemistic idea of transformation, which is, of course, strongly embedded in chemistry, as opposed to physics. In chemistry, you create new substances by processing other substances. In 1984, a book was published, written by Ilya Prigogin and Isabelle Stengers with the title Order out of Chaos. It described their scientific work with nonlinear chemical systems which were not in an equilibrium state. They discovered some chemical reactions which would produce effects in two directions. A chemical reaction normally goes in one direction, from state A to B. For example, if you put hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxid together, then you obtain sodium chloride, commonly know as salt. This goes only in one direction and is not reversible. Prigogine/Stengers discovered chemical reactions where A could go to B and B could go back to A in a non-linear way. This led them to conclusions about society and politics. We can use this as a metaphor for changes in society where somebody governs you and forces you to do this, but it can also be possible to go in the opposite direction. And all these idea of "grassroots" are related to this. When I read the book in 1984 I was still interested in chemistry, although I was studying music at this time. I found out that it could also be a very interesting metaphor for composition, that you open up to the unknown, taking randomness and chance into account instead of working in a deterministic way that everything can only go in one direction or following the one and only narration that you have conceived.

FC: Maybe I should add that Isabelle Stengers, whose book you just mentioned, is very well known here in the Netherlands, because she's a philosophy professor in Belgium, and some listeners may be familiar with her later books, such as "Living in Catastrophic Times". She's at the forefront of critical thinking about the Anthropocene and climate change. And of course the climate itself is a chaotic nonlinear system. So many of the things you mentioned apply to it. And now it seems that this contingency and chaos has reached you at the level of world politics. Was this the "butterfly effect" that changed your musical approach? Have you stopped composing? Is improvisation now your new way of working?

Coastline Session #6: Der Riss

Erwin Uhrmann: instant poetry

Karlheinz Essl: realtime sound

Recorded live at Studio kHz

23 June 20223

KHE: Composition in the narrow sense accompanies me constantly. Besides writing intrumental music (I just released the album ORGANO/LOGICS with all my organ works) I'm regularly going into my studio, setting up new Max patches, creating new pieces, which I put on YouTube, like my work-in-progress Coastlines, a series of live performance on my modular 0-COAST synth. I'm also inviting artists from other fields to contribute to it. I have a regular collaboration with the writer Erwin Uhrmann; we meet regularly for studio session where he invents texts and poems, along with my music. We sit on a table facing each other, and he's listening to my electronic sounds from the synthesizer. And then he starts speaking, and I react to what he's saying. So we are creating instant poetry and instant music in a free improvisation together. This is not yet published, it's still in an experimental state, but we will make our first performance later this year for a selected audience. It will place in the baroque library of the monastery in Klosterneuburg, a bizarre space with lots of books and globes. And then I was experimenting with a dancer, Andrea Nagl. We are collaborating since many years, making a project together, dance performances and room installations. Up to know I composed the music, always with computers. But recently we tried it out with my analog synthesizer - and it worked perfectly well. And most recently, I had an encounter with the visual artist Astrid Rieder for a so-called "trans-Art" performance. She was doing live painting when I was playing, and I reacted on her. And this was also very interesting experience!

KHE: This work is based on a long collaboration with Isabel Ettenauer. 10 years ago we released the album whatever shall be with my music for toy instruments and electronics.

A month ago, I published a CD with all my organ works on the label col legno. 11 pieces, partly also with electronics, performed by the wonderful organ player Wolfgang Kogert. This album ORGANO/LOGICS is also based on algorithm, and it has a lot to do with Athanasius Kircher and his idea of music machines. In the booklet, there is a text by Erwin Uhrman who spoke about my relationship with this Athanasius Kircher who also made a construction sketch of a hydraulic organ which is played by a water powered machine, so to speak.

Athanasius Kircher: Hydraulic Organ

in: Musurgia Universalis (1650), tom. II, vol. IX, fol. 347

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

FC: A footnote: Athanasius Kircher was a Jesuit monk in the 17th century who published monumental books with all kinds of fantastic machines, some of which he claimed existed in other cultures, but many of which were invented devices. He can also be considered one of the first algorithmic music composers, since he sketched a machine that would automatically compose music according to pre-set rules. Which, of course, was a big inspiration for algorithmic and generative music in the 20th and the 21st century.

Karlheinz, I think we could talk for hours. And maybe - next time you're in the Netherlands, just come to our studio in WORM!

KHE: Of course, I will surely come!

Throbbing Crystal, 2nd move

| Home | Works | Sounds | Bibliography | Concerts |

Updated: 4 Aug 2024