The Making of Coastlines

Karlheinz Essl im Gespräch mit Erwin UhrmannKünstlerhaus Wien, 18.10.2023

Karlheinz Essl im Gespräch mit dem Schriftsteller Erwin Uhrmann

Künstlerportrait Karlheinz Essl Where Sound Meets Nature and Nature meets Sound

A film by Sebastian Kubelka and Simon Essl

Karlheinz Essl: In Coastlines arbeite ich nicht mit den digitalen Mitteln, die mir seit über 30 Jahren vertraut sind und wo ich eine gewisse Souveränität im Umgang entwickelt habe. Seit einiger Zeit beschäftige ich mich mit modularen Analogsynthesizern, die ich künstlerisch befrage und erforsche, wie sie zu mir sprechen. Wenn man ein solches Gerät standardmäßig anschließt, klingt es immer gleich. Jeder, der sich in dieser Materie ein bisschen auskennt weiß, dass man modulare Synthesizer mit ihren unzähligen Steckverbindungen in abertausenden Kombinationen verschalten kann. Durch extrem unkonventionelle Verschaltungen habe ich meinen Synthie aber so umgepatched, dass er nunmehr ein chaotisches System bildet.

Und da kommen wir wieder zurück zur Natur und ihren Phänomenen. Aus der Chaostheorie wissen wir, dass Ordnung und Chaos sich gegenseitig bedingen und Teil eines Ganzen sind. Und das habe ich jetzt auf diesem Instrument. Was Sie hören, ist eine Art Sonifizierung eines gelenkten Chaos, das sich sozusagen selber gestalten kann.

Erwin Uhrmann: Ja, was wir gerade gehört haben, war ein Stück aus einer Serie mit dem Titel "Coastlines". Ein schöner Titel, sehr enigmatisch, wie viele deiner Arbeiten. Warum "Coastlines"? Hat das eine spezielle Bewandtnis?

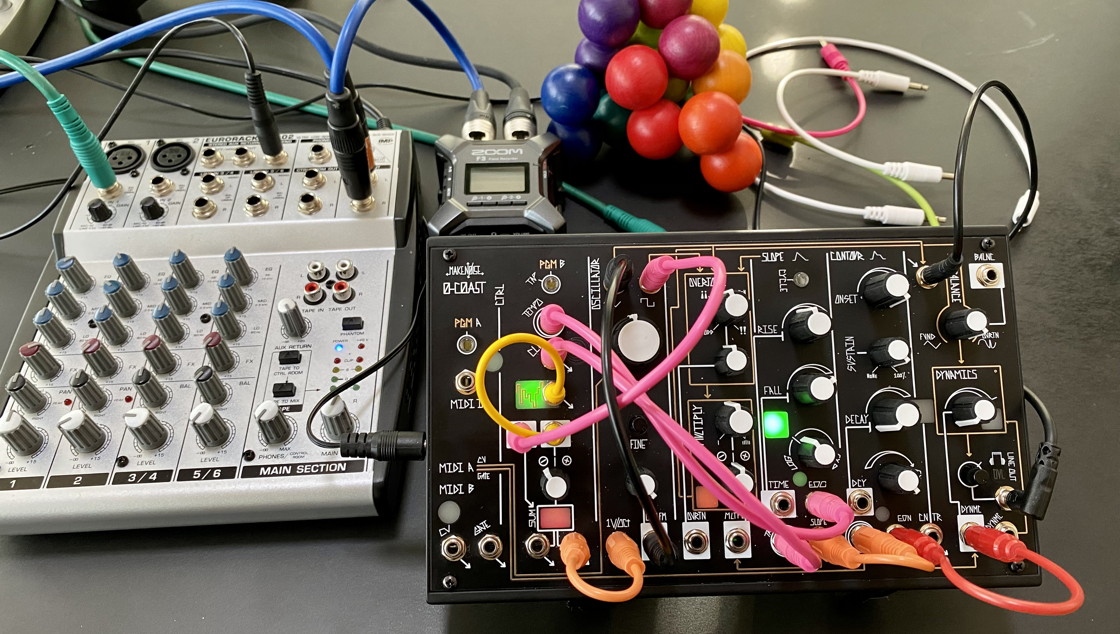

Make Noise 0-COAST analog synth

Setup: 3 Mar 2023 @ Studio kHz

KHE: Der Ausgangspunkt ist der Name meines Synthesizers, der "O-Coast" [Zero Coast] heißt. Dazu muss man ein bisschen in die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Synthesizers zurückgehen. Die Vorläufer sind in den 1960er-Jahren in Europa entwickelt worden, in den Studios von Köln bzw. Utrecht, wo mein verehrter Freund und Mentor Gottfried Michael Koenig gewirkt hat. Dort wurde ein großer Analog-Synthesizer als Studiosystem aufgebaut basierend auf kompositorischen Ideen, die aus dem Serialismus gekommen sind. Dessen abstrakten kompositorischen Konzepte wurden dann in Form von Hardware implementiert.

Zur gleichen Zeit gab es in Amerika - an der East Coast in New York - einen Ingenieur namens Robert Moog, der den ersten Modular-Synthesizer gebaut hat. Der füllte nicht mehr einen ganzer Raum, sondern war nur mehr so groß wie ein Kühlschrank. Mit etwa 14 Jahren habe ich mir eine LP mit dem verheißungsvollen Titel "Switched on Bach" gekauft. Auf einem Moog-Synthesizer hat ein Musiker namens Walter Carlos (nunmehr: Wendy Carlos) Kompositionen von Johann Sebastian Bach in einem Mehrspurverfahren eingespielt. Die Artikulationen der Barockmusik hat er fantastisch auf dieses elektronische Instrument übertragen können. Das war sozusagen der East Coast Synthesizer mit seiner ganz speziellen Architektur und den Möglichkeiten, wie die einzelnen Module miteinander zu verschalten sind.

Parallel dazu gab es an der West Coast in Kalifornien einen Komponisten namens Don Buchla. Er hat ein eigenes System entwickelt, das völlig anders funktioniert und das später auch Ernst Krenek benutzt hat. In seinem Nachlass im Ernst Krenek-Institut in Krems gibt es zwei von diesen Synthesizern, die mittlerweile restauriert sind und auch wieder gespielt werden können.

Zwischen diesen recht unterschiedlichen Architekturen positioniert sich eine kleine amerikanische Firma aus der Mitte des Landes, die ein Hybrid entwickelt hat, wo das Beste aus beiden Welten vereint ist. Aber dieses System ist dermaßen komplex, dass man es kaum durchschauen kann. Es ist für mich wirklich eine enigmatische Maschine, wo man sehr viel herumprobieren muss, ehe man überhaupt zu einem Klang kommt. Ich meine, dass ich mich in der Materie der elektronische Musik ziemlich gut auskenne - das gehört ja zu meiner Profession. Aber mit diesem Gerät hatte ich am Anfang gewisse Schwierigkeiten, weil da zunächst nichts rausgekommen ist, was für mich verwendbar war. Bis ich allmählich verstanden habe, dass ich das Gerät austricksen muss. So habe ich es mit sich selbst rückgekoppelt, und dann kommen plötzlich die wirklich spannenden Dinge zustande: es bilden sich chaotische Systeme, auf denen ich mich wie auf ein wildes Pferd setzen kann und versuche, dieses wildgewordene Tier zu reiten. Das heißt aber auch, jedes Stück entsteht im Moment und ist immer eine Improvisation. Was Sie heute bereits gehört haben, hat mich selbst auch überrascht! Ich habe mir natürlich eine Grundeinstellung für diesen Abend überlegt, aber wo wir jetzt hingekommen sind, das hat mich selbst verblüfft!

Der zweite Aspekt des Namens "Coastlines" bezieht sich auf ein mathematisches Modell, die Küstenlinie. Je näher man eine Küstenlinie betrachtet, desto komplexer wird sie und desto länger wird auch die Küste. Wenn man beispielsweise die Küste von Amerika auf einer Landkarte im Maßstab 1:100.000 abmisst, dann kommt man auf irgendeine Wert von so und so viel tausend Kilometern. Wenn man jedoch den Maßstab vergrößert - sagen wir auf 1:10.000 - und diese Küste nochmals nachfährt, ist sie nun mindest doppelt so lang. Und wenn man dann in die Realität geht und jedem Steinchen und jeder kleinste Erhebung nachgeht, dann ist die Küstenlinie tausende Mal länger. Wie bei einem Fraktal kann man hinein und hinaus zoomen und erhält immer wieder neue Details.

EU: ich würde es jetzt natürlich interessieren, nachdem das für dich jetzt auch Neuland ist, was du gerade gemacht hast, wie hast du das jetzt gerade selbst erlebt?

KHE: Das kann ich noch nicht sagen, ich war so weggedriftet! Ich werde es mir später anhören und mir dann Gedanken machen. Wie gesagt - ich war sehr überrascht!

EU: Das ist ja eine offene Arbeit, die immer weitergeht. Du hast vorhin erwähnt, dass immer die Einstellung, mit der du aufhörst, die gleiche ist, mit der der nächste Teil beginnt. Das kann man sich auch auf deiner Homepage anschauen, wo dieses work-in-progress in Form von YouTube-Videos dokumentiert wird. Alles ist im Prozess, nichts ist fertig. Also ich konnte mir das jetzt richtig gut vorstellen mit den Coastlines. Dieser kartografische Aspekt war für mich sehr deutlich erkennbar und sehr schön dieses ständige Zoom-in und Zoom-out...

KHE: Die Spannungen, mit denen man arbeitet, sind - technisch gesehen - Wechselspannungen, die vielfältig moduliert werden. Die Frequenzen dieser Spannungen umfassen einen riesigen Bereich zwischen ganz hohen und ganz tiefen Klängen, die so tief sein können, dass man gar keine Töne mehr hört, sondern nur mehr Knacksen oder Pulse. In diesem Spannungsfeld zwischen dem Rhythmus und dem Ton und dem Klang entsteht die ganze Musik. Diese Ideen hat der von mir sehr verehrte Karlheinz Stockhausen 1957 in seinem bahnbrechenden Aufsatz "Wie die Zeit vergeht..." theoretisch formuliert: alles, was wir in der Musik haben - die "Parameter" Rhythmus, Tonhöhe, Spektrum und Form - sind Zeitfunktionen auf verschiedenen Ebenen. Mit meinem kleinen 0-Coast Synthesizer kann ich das experimentell erforschen und sofort höher machen.

EU: Entscheidet es sich dann während der Improvisation, wie lange sie dauert? Oder wo der Endpunkt des jeweiligen Teils ist?

KHE: Ich mir habe keine bestimmte Dauer vorgenommen, irgendwas um die fünf Minuten. Ich wollte in erster Linie eine Klanggeste gestalten: eine Miniatur, die sich nicht unmäßig ausbreitet. Synthesizermusik neigt ja leider zur Geschwätzigkeit. Das sind oft Stücke, die wahnsinnig lang sind und Klangflächen ausbreiten, in denen man sich badet. Das wollte ich aber nicht, sondern ganz bewusst sehr gestische und extreme Ausdrucksvaleurs erkunden. Und wenn es dann so ist, dass da plötzlich eine Sache in die Höhe geht und dann immer mehr verschwindet, dann ist das doch ein schöner Schluss, oder?

EU: Ja, ein schöner Schluss und ein schöner Anfang für das nächste, oder? Vielen Dank.

Karlheinz Essl performing Coastlines live at Künstlerhaus Vienna on 18 Oct 2022

A film by Sebastian Kubelka & Simon Essl

Erwin Uhrmann (geboren 1978) lebt in Wien. Von ihm erschienen bisher die Romane Der lange Nachkrieg (2010), Ich bin die Zukunft (2014) und Toko (2019), die Erzählung Glauber Rocha (2011) sowie die Lyrikbände Nocturnes (2012) und Abglanz Rakete Nebel (2016). Gemeinsam mit Johanna Uhrmann schreibt er Sachbücher. Herausgeber der Reihe Limbus Lyrik. Zusammenarbeit mit Kunstschaffenden wie Moussa Kone und Karlheinz Essl in unterschiedlichen Projekten.

Karlheinz Essl: In Coastlines, am not working with the digital means that I have been familiar with for over 30 years and with which I have developed a certain mastery. For some time now, I have been working with modular analog synthesizers, questioning them artistically and exploring how they speak to me. If you plug such a device in by default, it always sounds the same. Anyone who knows anything about the subject knows that modular synthesizers, with their countless connectors, can be wired in thousands and thousands of combinations. But by using extremely unconventional connections, I have rewired my synth in such a way that it now forms a chaotic system.

And this brings us back to nature and its phenomena. From chaos theory we know that order and chaos are interdependent and part of a whole. And that's what I have now on this instrument. What you hear is a kind of sonification of a directed chaos that can shape itself.

Erwin Uhrmann: Yes, what we just heard was a piece from a series called "Coastlines." A beautiful title, very enigmatic, like a lot of your work. Why "Coastlines?" Is there a special meaning to it?

KHE: The starting point is the name of my synthesizer, which is called O-Coast [Zero Coast]. You have to go back a little bit in the history of synthesizers. The predecessors were developed in Europe in the 1960s, in the studios of Cologne or Utrecht, where my revered friend and mentor Gottfried Michael Koenig worked. There, a large analog synthesizer was built as a studio system based on compositional ideas derived from serialism. Its abstract compositional concepts were then implemented in hardware form.

At the same time in America - on the East Coast in New York - there was an engineer named Robert Moog who built the first modular synthesizer. It no longer filled a room, but was only the size of a refrigerator. When I was about 14, I bought an LP with the promising title "Switched on Bach". A musician named Walter Carlos (now Wendy Carlos) recorded compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach on a Moog synthesizer in a multi-track process. He did a fantastic job of transferring the articulations of Baroque music to this electronic instrument. This was sort of the East Coast Synthesizer, with its very special architecture and the way the modules could be connected.

Parallel to this, there was a composer on the West Coast in California named Don Buchla. He developed his own system, which worked completely differently and which Ernst Krenek also used later. In his estate in the Ernst Krenek Institute in Krems there are two of these synthesizers, which have been restored in the meantime and can also be played again.

In between these quite different architectures is a small American company from the middle of the country that has developed a hybrid that combines the best of both worlds. But this system is so complex that it is almost impossible to understand. It's really a mysterious machine to me, where you have to do a lot of trial and error before you even get to a sound. I mean, I know electronic music pretty well - it's part of my job. But with this device I had some difficulties in the beginning, because at first nothing came out that was usable for me. Then I understood that I had to trick it. So I fed it back into itself, and then suddenly the really exciting things come out: chaotic systems form, on which I can sit like on a wild horse and try to ride this wild animal. But that also means that every piece is created in the moment and is always an improvisation. What you have heard today has also surprised me! Of course I thought about a basic framework for this evening, but where we are now has surprised me myself!

The second aspect of the name "Coastlines" refers to a mathematical model, the coastline. The closer you look at a coastline, the more complex it becomes and the longer the coastline becomes. For example, if you measure the coastline of America on a map at a scale of 1:100,000, you get a value of so and so many thousands of kilometers. But if you increase the scale - let's say to 1:10,000 - and trace that coast again, it's at least twice as long. And if you go into reality and trace every little stone and every little hill, the coastline is thousands of times longer. Like a fractal, you can zoom in and out and get more and more detail.

EU: I would be interested to know, since this is new territory for you as well, what you just did, how did you just experience it yourself?

KHE: I can't say yet, I was so carried away! I will listen to it later and think about it. Like I said - I was very surprised!

EU: This is a work-in-progress that goes on and on. You mentioned earlier that the shot you end with is always the same shot you start with in the next part. You can see that on your website, where this work-in-progress is documented in the form of YouTube videos. Everything is in progress, nothing is finished. So I could really visualize that now with the coastlines. This cartographic aspect was very clear to me and very nice, this constant zooming in and out...

KHE: The voltages you work with are, technically speaking, alternating voltages that are modulated in various ways. The frequencies of these voltages cover a huge range between very high and very low sounds, which can be so low that you hear no sounds at all, just crackles or pulses. It is in this field of tension between rhythm and tone and sound that all music is created. These ideas were theorized in 1957 by Karlheinz Stockhausen, whom I greatly admire, in his seminal essay "How Time Passes...": everything we have in music - the "parameters" of rhythm, pitch, spectrum, and form - are time functions on various levels. With my little 0-coast synthesizer, I can explore this experimentally and take it right to the next level.

EU: Is it decided during the improvisation how long it will take? Or where the end point of each part is?

KHE: I didn't set a specific duration, something like five minutes. I mainly wanted to create a sonic gesture: a miniature that doesn't expand too much. Unfortunately, synthesizer music tends to be garrulous. Often it is pieces that are insanely long and spread out sound surfaces in which you bathe yourself. But I didn't want to do that, I wanted to explore very gestural and extremely expressive values. And if it's like that, that something suddenly rises and then disappears more and more, then it's a beautiful end, isn't it?

EU: Yes, this is a beautiful ending and a beautiful beginning for the next one, isn't it? Thank you very much.

Erwin Uhrmann (born 1978) lives in Vienna. He has published the novels Der lange Nachkrieg (2010), Ich bin die Zukunft (2014), and Toko (2019), the short story collection Glauber Rocha (2011), and the poetry collections Nocturnes (2012) and Abglanz Rakete Nebel (2016). He writes non-fiction together with Johanna Uhrmann. Editor of the series Limbus Lyrik. Collaborates with artists such as Moussa Kone and Karlheinz Essl on various projects.

| Home | Works | Sounds | Bibliography | Concerts |

Updated: 1 Sep 2023